An important goal of any design is to engage the consumer in the product. With a wealth of inspiration in other mediums, most notably film and literature, it’s unsurprising that a games design model based on how other entertainment forms engage their audiences has become commonplace.

This typically leads to the inclusion of plot elements more traditionally associated with movies or books. On a basic level, narrative structures are borrowed to aid engagement with any given audience. Even with this appropriation, it seems like this type of game design misses the mark more often than it hits anywhere close. But if they’re going to borrow from other mediums, game designers should at least finish what they started. Traditional plot requires an epilogue, a conclusion, an ending.

Studies into player engagement during Gears of War 2 showed discreancy between developers and consumers.

Plot isn’t something of which you can pick and choose what you’d like to borrow. It’s a literary framework that requires certain pieces more than others. Much like how a house isn’t finished until it has a roof on it, a game isn’t finished until you’ve put in the epilogue. Somewhere along the way, the idea of what an epilogue is has become muddled with the fact that where a game ends is, by definition, the end of the game.

For the most part, the first two thirds of the dramatic arc are kept intact by game designers: the inciting moment, or beginning, followed by some sort of exposition and rising action leading to a climax.This same kind of framework was used as far back as the Greek plays and the entire structure seems ingrained in our collective consciousness. It’s almost second nature for a person to construct a story this way. Unfortunately, a number of games decide to roll the credits directly following the climax. Gustav Freytag’s analysis of Shakespearian and Greek dramatic structure, Technik des Dramas (1863), shows that the plot isn’t completed with the climax – and that should apply to games too.

We still need some sort of falling action and dénouement or epilogue. But first it’s best to understand what each of these terms are and what they are not. Dénouement is just a fancy term describing the resolution of conflicts with a cathartic bent at the end of a story. It can function as a type of epilogue, but an epilogue is much more basically related to one simple word: closure. Each narrative requires closure. Even with sequels already in the works, there should at least be the illusion of closure.

While falling action and dénouement aren’t strictly necessary functions of the framework, it is a requirement to have the epilogue. Imagine the narrative structure of a game like a grand tent with multiple poles doing most of the heavy lifting. While it’s true that you can remove a few of the smaller ones or even rip holes in the tent itself, removing even a single load-bearing pole will cause the entire thing to sag.

21 Grams follows classic plot structure, even if it may seem like it doesn’t.

There’s an argument that, in an age of nonlinear narrative, we can chuck out the old rules. And it’s a flawed one. The best way to consider this is through a single piece in a related medium, the movie 21 Grams. Even though 21 Grams is, at first look, a deconstructed piece of postmodernism with little to do with any of the classic thematic structures, a second look reveals that it actually follows Feytag’s Pyramid fairly accurately. Even with disjointed narratives from different perspectives, there is an inciting incident within the first 25 minutes of the film and a climax 5 minutes before the end. It doesn’t matter how long the “third act,” which includes the epilogue, actually is. It only matters that it is included and constructed in such a way that it gives closure to the rest of the work.

To be fair, it seems that less than half of any given game’s players will finish the title. To put it in perspective, one article claims that the people behind BioShock were thrilled to have 50% of their players complete the game. So a lack of attention to the epilogue, from a cost-benefit analysis, is understandable. That doesn’t mean it’s acceptable. Realizing that the first level of a game (played by every owner) receives more attention than the last (played by perhaps 10% of owners) doesn’t equate to being satisfied with the outcome. If I were to hazard a guess, I’d wager that this is just the nature of the medium. Even relatively short games can clock in between 10 and 20 hours and, if one weren’t concerned with the narrative, short bursts of play without actually making progress might be the norm.

As an example of a relatively good epilogue, Halo 3 doesn’t end after defeating the Covenant but after a longer cut scene designed to provide resolution. While it might not be the most engaging epilogue, watching the end of a trilogy is moving. There are arguments as to whether or not cut scenes can continue to keep you as engaged as gameplay, but that’s for another column. You learn of the fate of Arbiter, Earth and most important Cortana and Master Chief. While the Legendary ending does leave it open for a sequel, it doesn’t ask more questions than it needs to ask.

Even BioShock, certainly a highly regarded game, has a third act that essentially consists of a number of fetch quests that result in the final confrontation with Fontaine. And this all occurs long after what many consider the climax, when you finally reach Andrew Ryan. After this major twist, there doesn’t seem to be much impetus to finish it up. For the avid moviegoer, it’s that moment when you look at the screen and wonder how much longer the film will go on before it ends. In BioShock, there’s a whole protracted act to go before, finally, a brief cut scene that offers a resolution of sorts, but not one that satisfies.

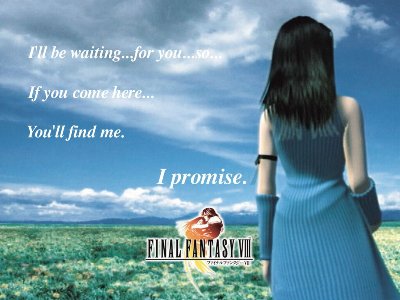

Final Fantasy VIII: Worst ending, best epilogue?

That doesn’t even open the can of subjective worms about whether these were “good” epilogues. For a number of people, the ending of Assassin’s Creed is one of the absolute worst. Final Fantasy VIII may well have the absolute worst ending of any Final Fantasy game and yet the best epilogue. If you’ve never seen the sequence that rolls during the credits, then you’ve missed out on one of the best epilogues out there. Even with the subjective nature of whether an epilogue is actually enjoyable, engaging and any number of other important aspects, it’s obvious that we have a long way to go with games still ending directly after the final battle.

”