We’ve all seen them. In nearly any game you play there will be a progress bar of some sort. Its implementation is varied, ranging from how how tech-savvy you are in Arcanum to faction support in World of Warcraft. Typically and especially lately, they have been used in conjunction with morality.

While the impact of moral choices in gaming has been argued to the point of exhaustion and while there appears to be strong vocal disinterest, designers continue to implement progress bars indication how actions sway you towards one moral side or the other. This mechanic is oft accompanied by a unambiguous window telling you the quantity of good or evil achieved. This direct quantification produces choices based on which moral way you want to go rather than actually meaningful decisions.

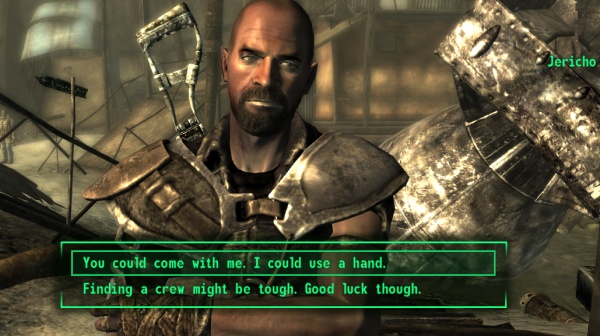

Fallout 3 explicitly reveals the moral consequences of your actions at every step.

In his Gamasutra article, James Portnow of Divide By Zero Games talks about different reasons for this kind of mechanic and possible solutions. He suggests that, designers could “just present ambiguous moral choices using the same system that we use right now for unambiguous choice, but hide the statistical effects. That is to say: simply don’t show ‘+2 to paragon’ every time the player does something nice.”

One possible interpretation of Portnow’s statement is that designers should hide the actual moment or amount of morality shift from the player but keep the statistical data present somewhere else. This kind of design reminded me of when I discovered that I had contracted a sexually transmitted disease in Fable II, having not been notified of the actual exact moment. By finding out later in a more lifelike fashion than I expected, the lack of knowledge on my part certainly evoked a different set of emotions than the norm. Even with this change, the player can still seek out and find their progress within the menus presented to them.

That sort of change doesn’t treat the problem but merely a system. If game designers decided to hide the notification, why not hide the bar entirely? Without a bar to check our progress on combined with the elimination of notifications, choices not only become ambiguous but impossible to quantify from a player’s perspective. Maybe this sort of thing already exists, but I’ve not yet encountered a game that does exactly as stated above.

Of course, this would require decisions beyond the simple and absurd like choosing between saving the children and eating them. This may sound like hyperbole, but take a moment to consider BioShock in which you’re given the choice between saving and harvesting Little Sisters. Or even between blowing up Megaton and not blowing up Megaton in Fallout 3. The difference is night and day.

Does the Little Sister dilemna really represent moral choices?

It’s not as if hidden values haven’t been used in the medium before, either. In Pokémon, each little monster you catch has their own set of Effort Values (EVs) associated with them. These EVs are determined by a variety of factors such as the Pokémon’s nature, but are not expressly given for players to see. Instead, they can be extrapolated from said factors but otherwise have a profound yet hidden influence on the growth of a player’s team. One look over at Smogon is enough to see that these hidden factors have actually added a depth to the gameplay that a casual glance might fail to reflect.

Regardless of the mechanic used, any system that involves supposed moral choice requires the designer to quantify and label actions based on their own scale of morality. Even if the bar was completely hidden, it would still have to exist. This becomes even more complicated when designers include oddly non-moral decisions as factors. Not to pick on Fable II, but eating broccoli is in no way a moral choice (it really depends on how you eat it – Ed).

And really, blaming everything on progress bars is a bit of a stretch. It’s not the fault of the mechanic that game designers continue to implement it. But when you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

”