I don’t have solicitors. I don’t even have a solicitor. But in the frequent cases when companies were a bit too eager to dig into my pocket anew, the “let me consult my solicitor” argument works wonders – especially when the employees know they are asking for something certainly necessary or not certainly legal. Then again, if I’m left with no option but to persist with a software or a retailer unless I want to be stripped of a group of products altogether, what good will my fictional elite squad of tuxedo-clad Oxford law graduates possibly achieve?

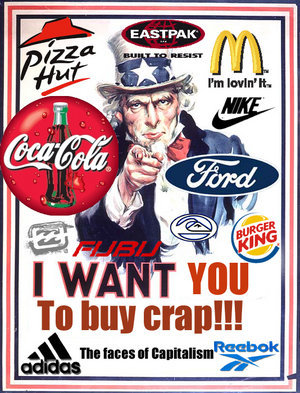

Capitalism pre-facelift – the less advertised appearance.

- We are left with no choice.

Venturing for products in a monopoly-driven industry is a question of choosing between a retailer offering a few very fashionable pieces and a shop where you have heaps and heaps of all kinds of clothing. I realise the increased risk of committing a fashion faux pas in Primark, but I also have the pleasure of that choice, even if it shall resolve in my looking like a hooker.

Though we often complain of too much choice, I am convinced too little choice would ultimately pose an even worse situation. Human beings have always been obsesses with novelty – there’s no better example of this obsession than the pleasant sadistic pang in one’s stomach when our friends state they had no idea about “this new [insert band name, trend or book]” and we feel oddly content because we may now subtly, but effectively bully them into admitting they don’t keep up with today’s innovations. That is why a game industry limited to only the most popular releases with the most successful advertising and sponsors would very quickly bore us to death – or at least, its own death. In this process, computer games would also become prone to seasonal “fashion”– something that would seem impossible a decade ago when for hormone-driven teens, gaming was a rebellion against the superficial and judgemental lifestyles other people from this certain age group often practice. Traces of this are already evolving, and the character of the gaming subculture is slowly crumbling. The very concept of everyone playing the same games and hitting the shops for the “popular” big-money titles is an antonym of why the games industry is constantly developing, morphing and seeking new ideas – or at least claims it is.

2. A monopoly can request anything.

Assuming a situation where we are left with one exceptionally superior game provider of new products releases that successfully dominates an industry, a Monopoly in its crystallised state, our prospective is rather miserable. Though we are not slaves to any market (though many people would argue that in today’s “Buy this!”, “No, buy this!” culture we are), we also have no alternative should we be unhappy with the services provided. We cannot scoff at the unqualified Tech Support from a further unidentified Asian region, or say, “Fine then, I’m afraid I have no choice but to move to [insert name of a rival company].” Finally, even my personal favourite fails and I’m deprived of the pleasure of announcing: “In that case, should I contact my solicitors or will we be able to sort this out?” Now, I don’t have solicitors. I don’t even have a solicitor. But in the frequent cases when companies were a bit too eager to dig into my pocket anew, this argument works wonders – especially when the employees know they are asking for something certainly necessary or not certainly legal.

Then again, if I’m left with no option but to persist with a software or a retailer unless I want to be stripped of a group of products altogether, what good will my fictional elite squad of tuxedo-clad Oxford law graduates possibly achieve? Certainly not my personal satisfaction. In the end, in a monopoly driven games market, if I want to stay in the game – so to speak – I have to put up with any inconvenience. Along with the unpleasant fact that those may multiply like fleas.

3. Underground stays underground – and the industry becomes a very tightly sealed box.

This particular point I feel very strongly about because my own ambition is to achieve a Bachelor degree in Games Design, a craft I see as the compromise between art and an actual income which is probably not probable any time this century with just art itself. But predominantly, I am an observer and a gamer – I believe a varied market divided into bigger and smaller companies, but still sensible enough to give smaller and more experimental projects a chance to break through, is probably most gamers’ idea of heaven. Though neither money nor public attention is ever evenly distributed in capitalism, we can talk about a normal and desired situation within a market only if smaller enterprises have a chance of commercial success with enough luck, patience and hard work.

“She doesn’t know what she’s talking about,” you may think. “Portal was a small project, and look at it now!” Well, yes – there is no denying that it was not a fully developed game and neither was it done by an amount of personnel usually needed for larger projects. However, let me remind you that Portal was indie in its most superficial layer of appearance only – it was developed in collaboration with VALVe, one of today’s largest and most commercially successful companies, then advertised and sold through Steam and Orange Box, the first being a property of VALVe and the second, a pack of games all developed and owned by – oh, this is getting repetitive – also, inevitably, VALVe. And indeed, it was a good game, a fair game with some uplifting freshness, but its primary objective was to awaken a positive response to a domineering software and company – to present that a market slowly dominated by one group is opened to unconventional projects, to less commercial means and new, fresh designers.

Meanwhile, I remain unconvinced.

4. The magic is gone.

In the same way I love Christmas, I love the memory of unpacking my first-ever game; the rattling of the CD in the enigmatic packet, the curiosity until we open the box and the mystery is released into the air. Jolly good show. I even remember what my first game was – The Sims, and no, not The Sims 2 or The Sims 3, but the vintage classic itself. For a young kid I was at the time, who never played, let alone held, a computer game, this was an absolute first, and like all of those, possessed the same impatient quality of unwrapping Christmas presents, while finding someone who played the same game – a brother in arms… er, games – was always a curious occasion, too.

Today, gaming isn’t reserved to a certain group of in-jokes and its own rituals, neither is it represented by any real community and the industry lacks the new, thick substance it possessed in those earlier years. There are still great events out there organised so people with the same weirdness threshold can discuss newest releases, dress up as anime characters and bond through killing each other (on Xbox, of course). Nevertheless, though these groups are certainly not shrinking, their quality is. I’d even risk going as far as saying that because the industry is globalising and commercialising like everything else, the advance of technologies and graphics may be growing, but the class of story-telling is contracting. To game enterprises, and most importantly, to those financing the game enterprises, we have become just another target, a clientele with average needs, average expectations and average budgets they are aiming for and ticking off on the planning sheets. We are a marketing target worth big bucks – everything about our needs is estimated and every new project is optimised to suit these needs. The problem here is that never, ever can you attempt to please everybody without creating something deprived of that little, special word – magic.

5. And if the monopoly falls…

Imagine you only have one grocery shop in your town – and that you cannot travel anywhere else for your food. The very restriction and loss of variety would drive you mad and your fridge quite empty, but the real bad news would approach if the shop was to declare being penniless and the restriction rules would still apply. The only thing left to do would be to dig out the rosary beads and give out rations.

Hopefully, we will never have to face this problem in Europe or America as we have enough food in those regions to feed the starving nations three times over – or at least, much more food than we sensibly need. Meanwhile, we are already under such restrictions in other areas – as the recession progresses, more and more business juggernauts announce bankruptcy, many of which own large companies which, in the meantime, own smaller firms, and so on. This is a pattern incredibly difficult to change as the long history of capitalism with decades and decades of tradition behind it assumed such structure for maximum profit – it’s also quite destructive at worst and monothematic at best. Even if we are not in danger of a fall of the gaming empire anytime soon as it’s an industry worth billions and millions, one that wouldn’t be easily allowed into ruin, the dictatorship makes us completely cut off from having any influence on today’s quality of products, even though they are made with our money. In the future, we may be facing major quality issues, both from distributors and creators.

But of course, we may be facing them already.

Catgamer is the authot on the catgamer blog. Visit her at http://catgamer.wordpress.com/