I remarked in my last article for TGR that games arguably lack “propositional content” when compared to other, more established forms of mass media. That is to say, games generally make fewer points about the the world and about life than the average novel, film, or television series. There are many potential explanations for this propositional gap, often linked in to the relative youth of games as a medium of communication, and perhaps also to the perceived or actual youth of the average gamer. One area in which the propositional gap might be said to be particularly wide is in the use of media for political communication. For as long as it has existed, the mass media has always been used by groups or individuals seeking to use it as a lever for political change. But in the few decades during which videogames have been a significant cultural force, very few attempts have been made to use games to communicate political ideas. Now seems as good a time as any to speculate as to why. Are games a surprisingly untapped route to making points about how things are run? Or does the nature of the medium make games unsuitable for disseminating explicit political ideas – might this explain the few attempts to do so?

For a long time now, it has been clear that games do have uses beyond mere entertainment. One organization which has realized this more than most is the United States army, who have used games as a tool for recruitment (America’s Army) for training (many, for example UrbanSim), and even to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (Full Spectrum Warrior). In more civilian applications, the adventure game series Myst has been experimented with in school lessons, and the controversial evangelical Christian game Left Behind: Eternal Forces and the family-friendly The Bible Game are among a few works which have sought to explore religious issues in a playable format. So far, however, the main outlet for politics in games has been a number of somewhat dry political simulations, like Positech’s Democracy series.

In fairness, there have been at least a few examples of games seeking to make explicitly political points, often in the arena of online, browser-based games. Take the extraordinary Bushgame for example: released in 2004, this ambitious side-scrolling political platformer tasked the player with controlling figureheads like Hulk Hogan, Howard Stern, and Mr. T to try to halt the apocalyptic plans of the Bush administration. The game’s over-the-top satire involved the robot Voltron (“fueled by oil and the blood of foreigners”), Paris Hilton, and an attempt to “stop Barbara and George [Bush] from procreating this nation into devastation!” Crassly hilarious as it frequently was, Bushgame was distinctive especially because it combined its outrageous political humor with moments of genuine seriousness, including graphical and textual demonstrations of some of the worst excesses of George W. Bush’s first term in office. One section, for example, explored the politics of the US’ changing budget deficit over time – learning about this while playing as Hulk Hogan was a curious experience.

The first few years of the new millennium brought with them an explosion of political flash games, most of them related to the 9/11 and the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Often these were in remarkably poor taste, rife with clichés and hastily hacked together to capitalize on bloody recent events. One or two, though, made genuinely intelligent points in an innovative way. Among the most concise and striking of these was the anti-game September 12th, which opens with a striking title card:

“This is not a game. You can’t win and you can’t lose. This is a simulation. It has no ending. It has already begun. The rules are deadly simple. You can shoot. Or not. This is a simple model you can use to explore some aspects of the war on terror.”

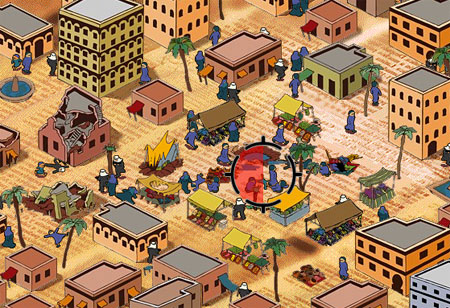

The game sits you above a Middle Eastern town and arms you with a crosshair. Among the civilians below lurk a few rifle-wielding terrorists; if you choose to fire your rockets at them, the weapons impact only after a delay, invariably inflicting civilian casualties. People weep over the bodies, wailing relatives line the little cartoon streets. Before long, it becomes clear that the survivors are swelling the ranks of the terrorists. Violence has become an unending cycle, further violence only pouring more fuel on the fire. Unsurprisingly, this kind of message was conspicuously absent during a sequence in Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare which was played out from a near-identical perspective. That a game as simple as September 12th is able to make such an incisive and fundamentally true comment about the nature of the so-called “War on Terror” is a testament to the immense potential of games to comment interactively on the political and ethical issues of the day. But also, it raises the possibility that interactive media must be closer to illustrative, symbolic simulations than to games in order to make serious points.

Conventional political simulations like Democracy generally depict politics as a set of mechanics without commenting on them. However, it could be postulated that the principles of such simulations may have potential usefulness as political communication tools, which could communicate messages more ambitiously, if not as elegantly, as September 12th. For example, imagine a simulation developed by or for a political campaign group advocating electoral reform. The game’s emphasis would be on exploring the differences between different sets of voting rules, making players contest elections under those rules, and trying to convince the player that a change ought to be made in the real version of their country once the current real rules had been shown as demonstrably unfair in the game. Such a game would be difficult to make genuinely entertaining, but a campaign group could consider releasing it free online, and promoting it as much as an educational tool as a reform advocacy one.

The ability of a few thoughtful outsiders to make deeply thought-provoking games oozing “propositional content” about politics has been demonstrated by the likes of Newsgames, developers of September 12th and its similarly impressive sister-game about the Madrid bombings of 2004, Madrid. It also seems feasible that more complex simulations could challenge a player’s thinking about less explicitly emotive political issues, such as electoral reform. But campaign groups that could benefit from such a simulation are also outside the political system. Could games also have communication benefits for politicians themselves?

Politicians may have been able to adapt relatively quickly to innovations like YouTube and Twitter, recognizing them as important tools for the dissemination of ideas, but it’s difficult to see ministers, candidates and political parties being able to get a similar handle on videogames. The interactivity of a game breeds unpredictability, always a hazard for the increasingly media-savvy, meticulous, and stage-managed nature of 21st-century campaign politics. In addition, politicians may be reluctant to encourage voters to participate in virtual elections as they might fear that it could discourage people turning out on the day in real life. Party-political communication and PR is a veritable minefield, and adding a new dimension to the process – especially one as complex and interactive as gaming – probably presents too many risks and uncertainties to politicians for us to be able to expect any party-political games for the foreseeable future.

Having said that, there may yet be a purpose for games as far as reaching out by politicians is concerned – this could be not so much in the sphere of campaigning, but at an earlier stage – that of policy-making. It is conceivable that a game could be designed which could help a political party better understand the policy orientations of voters, allowing them to more accurately target their campaigns and manifestos. Such a game could act as a kind of high-concept playable survey, teasing out the policy preferences of its players and communicating them via the internet to the politicians. The powerful feedback mechanisms exhibited by Steam help developers understand how gamers like to play their games; a carefully calibrated political game networked in this way could help politicians learn how voters would like their country to be run. Enticingly, such a method could potentially give a far more nuanced snapshot of voter policy preferences than even the most elaborately constructed survey. Better still, if by some miracle the game could be made entertaining, the interactive survey would complete itself, proliferated around the net by intrigued and – crucially – entertained voters.

The meteoric rise of games as a cultural phenomenon is just beginning to be noticed by the people who already have their hands on the levers of power around the developed world, but it is to the future we must look to glimpse the true potential of games as a medium of political communication. Before long, young people brought up on a diet of games, enthralled by their possibilities, will be a vital political force. When this occurs, we might begin to see the interactivity, dynamism and verve of the videogame being brought to bear on the political issues facing our societies. As ever, what will happen then is anyone’s guess… but on the existing evidence it is not so difficult to imagine a world in which games and politics draw closer together.